From the Publisher

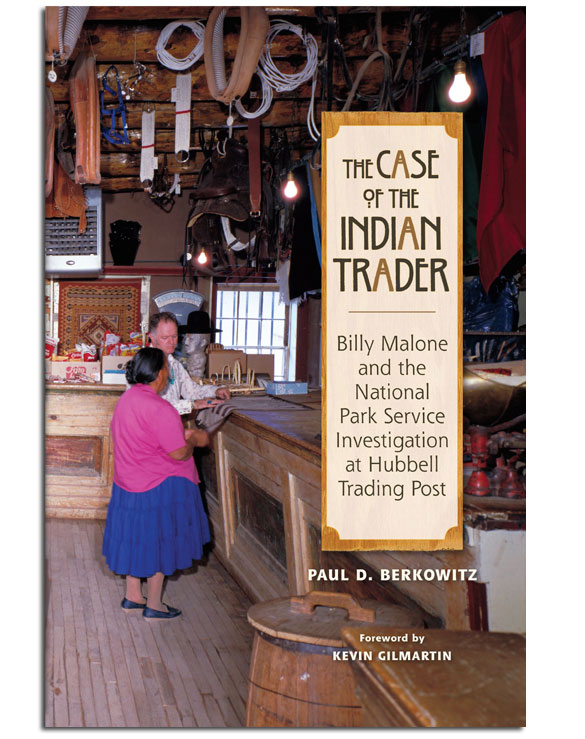

This is the story of Billy Gene Malone and the end of an era. Malone lived almost his entire life on the Navajo Reservation working as an Indian trader; the last real Indian trader to operate historic Hubbell Trading Post. In 2004, the National Park Service (NPS) launched an investigation targeting Malone, alleging a long list of crimes that were “similar to Al Capone.” In 2005, federal agent Paul Berkowitz was assigned to take over the year- and-a-half-old case. His investigation uncovered serious problems with the original allegations, raising questions about the integrity of his supervisors and colleagues as well as high-level NPS managers.

In an intriguing account of whistle-blowing, Berkowitz tells how he bypassed his chain-of-command and delivered his findings directly to the Office of the Inspector General.

Winner of the 2012 Independent Publisher Book Award for Best Regional Non-Fiction (Mountain West)

2012 New Mexico-Arizona Book Award Winner

Excerpt from “The Case of the Indian Trader”

Later that afternoon Okerberg and I drove to Gallup, where we were scheduled to meet with Malone at his residence and return the property we now had.

Malone and his wife, along with one of their daughters and her husband and their two children, were all living together in their tiny two bedroom adobe bungalow located just a few blocks south of the main drag (Route 66) running through town. This was Okerberg’s first opportunity to meet Malone. He, too, seemed struck by Malone’s mild and almost meek stature and demeanor. We were introduced to Malone’s wife, Minnie, as well as their daughter and her children, who were obediently playing in the adjacent kitchen. We carried the boxes inside and stacked them in the tiny living room. We asked Malone to go through the contents so that he’d be comfortable signing the new property receipt I had prepared. That receipt acknowledged that at least one box of seized property, including an unknown quantity of cash, was still missing.

Before leaving, I opened my brief case and pulled out the letter I had received a few days earlier from AUSA Long, dated January 4, 2007. More than a year after I’d inherited the Hubbell Case, and more than two and a half years after the National Park Service launched its investigation targeting Billy Malone, the U.S. Attorney’s Office finalized their decision. Based upon all of the evidence, good and bad, they had decided to close their case files and not pursue a prosecution.

After expenditure of nearly a million dollars, not a single charge would be filed against Malone in the Hubbell Investigation. I felt that I had done my job, but it was most certainly not the outcome my own supervisors had anticipated or desired when they assigned me to take over the investigation. It was equally certain I would not be receiving any accolades, awards, or even thanks from the National Park Service for my work.

I pulled Malone aside, handed him the letter, and told him “It’s over.” The NPS investigation and the government’s case against him was closed.

Malone’s eyes welled up as he read the letter. He reached out to shake my hand, quietly saying “thank you,” and then gave me a hug. It was one of the most remarkable and gratifying moments I had experienced in my entire 33-year career.

Radio interviews

KSJE – Write-on Four Corners

November 7, 2018

Santa Fe Radio Cafe

August 24, 2011

In the news

The Journal

July 20, 2016

By Jim Mimiaga

Cortez, Colo. – As part of the Four Corners Lecture Series, Paul Berkowitz, a Dolores author and former criminal investigator for the National Park Service, relayed how he exonerated Billy Malone, an Indian trader falsely accused of embezzlement.

At a packed house July 14 at the Center for Southwest Studies at Fort Lewis College, Berkowitz unraveled the legal drama documented in his tell-all book “The Case of the Indian Trader: Billy Malone and the Park Service investigation at Hubbell Trading Post.”

Malone, a respected trading post operator on the Navajo Nation, got caught up in a botched Park Service investigation that left him reeling until it was assigned to Berkowitz, who turned the case around.

“If it weren’t for him, they would still be turning over rocks trying to pin something on me,” said Malone who joined the Fort Lewis College presentation.

The case centers on the Hubbell Trading Post, a national historic site and working trading post in Ganado, Arizona, that Malone managed for decades.

The trading post is run by the by the nonprofit Western National Parks Association, which donates a portion of revenues to the Park Service. During an audit, the Western parks association reported that millions of dollars were missing and accused Malone of government theft.

In 2004, the Park Service began investigating Malone for government fraud and theft. He was fired, and had his home raided was by the Park Service, which confiscated hundreds of rugs and a jewelry collection Malone had earned through a lifetime in the trading business.

“I was devastated, totally blindsided. It knocked me down for 2-3 months,” he said.

Read the full story here or here. (PDF)

Navajo Times

By Bill Donovan

Special to the Times

WINDOW ROCK, April 15, 2011

Paul D. Berkowitz, the author of “The Case of the Indian Trader,” describes his book as being about “the end of an era in the Old West.”The fact that it took place in Ganado, Ariz., less than a decade ago makes the story of the National Park Service’s attempt to put Bill Malone behind bars and take control of his extensive personal collection of Navajo rugs and jewelry a tale that most people on the reservation can relate to.

Malone at the time was the manager of the Hubbell Trading Post, the oldest trading post on the reservation. It had been purchased some 40 years before by the NPS from the Hubbell family. The NPS was under orders from Congress to operate it as an authentic trading post under the supervision of a real Indian trader.

Probably no one other than Berkowitz could have written the full story of what happened to Malone than Berkowitz. He was a senior investigator for the NPS who was given the job in 2005 – 18 months after Malone’s collection was confiscated – to prove that Malone had violated the government’s trust and either stole or misappropriated his personal collection while he was running the trading post.

Berkowitz, who retired from the NPS shortly after concluding the Malone investigation, said during a telephone interview from his home in Colorado that when he was first approached about the idea of getting involved in the investigation, he assumed that there was some validity to the accusations.

Then he did something none of the other federal investigators had done – he called Malone to get his side of the story.

Read the full story here or here. (PDF)

High Country News

May 2, 2011

By Andrea Lankford

Calling the National Park Service case against Billy Malone “misguided” is a kindness. Others use words like “corrupt” or “fiasco” when speaking of the bungled federal investigation that cost taxpayers nearly a million dollars, ruined the reputation of one of the last old-time Indian traders and may have transformed an authentic Indian trading post into nothing more than a gift shop.

This upsetting story begins in 1965, when National Park Service historian Robert Utley proposed to agency director George Hartzog that the Hubbell Trading Post, which was about to be designated a National Historic Site, would best be operated as a “static exhibit, with period merchandise on the shelves.”

Hartzog, it’s reported, erupted into a “colorful” tirade and cursed Utley’s suggestion. No way was the trading post on the Navajo Reservation going to be “another goddamned dead embalmed historic site.” Congress agreed, and the agency’s mandate was to manage Hubbell Trading Post as a living, breathing trading post with an authentic Indian trader running the place. It would sell everything from tools to Navajo rugs and serve the community instead of catering to tourists.

Some equate “living history” with Civil War re-enactors marching across the battlefields of Gettysburg. But the Hubbell Trading Post was supposed to be different. The Indian trader and his Navajo patrons wouldn’t need costumes, because the trading post wasn’t “living history” as much as it was history still living.

In 1981, Billy Malone accepted the trader position at Hubbell Trading Post, and the Park Service felt lucky to have him. The gentle and soft-spoken Malone was born in Gallup, N.M., but lived on the reservation most of his life. Married to a Navajo woman for over 40 years, he was a white man who lived like a Navajo, spoke the language and understood the local customs.

An Indian trader in the 21st century works under unique circumstances. Many of his suppliers and customers don’t have bank accounts; they buy and sell on a cash or barter system, and the trader is expected to hold valuable rugs or jewelry as collateral for no-interest loans. It has been this way for over a century.

Read the full story here or here. (PDF)

Tucson Weekly

June 16, 2011

By Jon Shumaker

Everyone who has ever watched a Western knows all about trading posts—or thinks they do. Reality is far more interesting than any Hollywood hokum, as we learn in The Case of the Indian Trader.

The Navajo were crushed by U.S. government forces led by Kit Carson in 1864. The tattered remnants of the tribe were forced on a genocidal death march—the Long Walk—when some 8,000-plus Navajos were forced to walk more than 300 miles from their homeland in the present-day Four Corners region to Fort Sumner at Bosque Redondo, N.M. Many died.

During captivity at Fort Sumner, the Navajo were introduced to government commodities. In 1868, a treaty was signed, and the Navajo were allowed to return home. Clever merchants figured out there was a market for Indian arts and crafts, and there was money to be made by trading basic supplies for handcrafted items like rugs and jewelry. By the turn of the century, there were 30, and by 1948, there were about 100 trading posts on the Navajo Rez.

One built in Ganado, in 1870, was purchased in 1878 by John Lorenzo Hubbell and became known as Hubbell Trading Post.

The number of old-time trading posts declined in the 1960s and ’70s for a variety of reasons. The Hubbell family managed to cut a deal in the mid-’60s for the federal government to purchase what had become the oldest continuously operated trading post in the West and hand it off to the National Park Service (NPS), who would continue operating Hubbell in the traditional manner as a sort of “living history” national historic site.

DailyLobo.com

June 20, 2011

By Andrew Beale

The words “Special Agent” may conjure images of James Bond’s Aston Martin zooming through the alleyways of a small Italian villa, but they’re not usually associated with park rangers.

A new book from UNM Press will prompt some people to rethink

their conception of National Park Service employees. The book’s author, former Supervisory Special Agent Paul Berkowitz, said park rangers investigate the same things as criminal investigators do in cities.

“Murder, rape, robbery, lots of drugs … there is crime in parks at the same level and to the same degree that there is anywhere.

Crooks come to parks just like they go anywhere else,” he said.

Berkowitz’ book sheds light on intrigue and shady dealings within the Park Service that would fit perfectly in a bestselling spy novel.

In The Case of the Indian Trader: Billy Malone and the National Park Service Investigation at Hubbell Trading Post, Berkowitz details his last case as a special agent with the Park Service, a case that caused him to resign after leveling charges of incompetence and wrongdoing at some of his superiors within the agency.

The book focuses on an investigation launched into Billy Malone, the operator of the Hubbell Trading Post from 1981 to 2004.

Malone was accused of embezzlement and, later, theft of a large number of rugs and other Navajo crafts, accusations that were found to be false during Berkowitz’ investigation.

Read the full story here or here. (PDF)

Albuquerque Journal

June 29, 2011

By David Steinberg

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — Paul Berkowitz, a criminal investigator for the National Park Service, took over a case after another investigator spent 18 months and hundreds of thousands of dollars, but found no evidence to file charges against Billy Malone, the longtime and respected trader-manager of the famed Hubbell Trading Post in Ganado, Ariz.

Berkowitz said he was told to find something to charge Malone with, but don’t use too many resources.

“At that point, I assumed there must be some validity to the allegations (of embezzlement or theft) because when a case was going on this long and given the magnitude of the allegations, there must be something there,” he said in a phone interview from his home in southwestern Colorado.

Two weeks into his probe, Berkowitz saw flaws in the allegations; the more he probed the stronger he believed the Park Service and the Western National Parks Association, which operated the trading post for the NPS, committed improprieties.

Berkowitz’s investigation is the basis for the new book “The Case of the Indian Trader.”

Navajo-Hopi Observer

July 29, 2011

By S.W. Benally

Many older Americans became familiar with the National Park Service as children through the popular cartoon “Yogi Bear,” chronicling the tale of a clever picnic-basket stealing bear versus a friendly if not distraught park ranger. Others have been fortunate to visit various national parks through family vacations, and have met helpful, friendly staff in person. As a whole, the National Park Service (NPS) is viewed with fondness and respect.

But like other federal agencies, it seems there is a darker side to the NPS.

In his capacity of a NPS special agent, Paul Berkowitz was responsible for investigating serious crimes committed in the national parks. He was asked to take over lead in the investigation of Billy Malone in late November of 2005.

“Berkowitz describes the culture of the agency and takes the reader through the history of how the NPS has evolved into an atypical bureaucracy, unique in all of government for both its idealistic mission and for the image it has cultivated with the American public. But that culture and public image has left the agency vulnerable to abuse by ambitious and unscrupulous employees, supervisors, and managers – including law enforcement personnel – whose own influence and raw political power has enabled them to operate with alarming levels of autonomy and freedom from meaningful oversight and accountability,” writes Kevin Gilmartin, PhD, in the forward to The Case of the Indian Trader. (Gilmartin is a behavioral scientist specializing in police ethics and crisis management.)

Read the full story here or here. (PDF)

National Parks Traveler

July 27, 2011

By Kurt Repanshek

In its long-hidden report on the National Park Service’s mistake-prone investigation of the business side of Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site the Interior Department’s investigative arm cites significant missteps by Park Service investigators and raises questions of the propriety of both the Park Service and Inspector General’s probes.

Among those questions:

- Why was no legal action taken against Park Service Special Agent Clyde Yee after it was determined that he “submitted false information on (the) search warrant affavit and did not properly account for cash and evidence seized”?

- Why did the assistant U.S. attorney general in Arizona who was handling the case decline to prosecute the special agent, and what “administrative remedies” did the Park Service take against him?

- What has the Park Service’s Intermountain Regional Office done to remedy what the Inspector General’s report termed “an inappropriate relationship between NPS and WNPA (the Western National Parks Association) during the NPS investigation”?

- Why did it take a lawsuit to get the Inspector General’s office, which finished its investigation in 2008, to release its final report?

Read the full story here or here. (PDF)

August 10, 2011

Much buzz this spring was about the publication of a book that exposed a great injustice in Indian Country. Written by Paul Berkowitz, a self-avowed “whistle blower” for the National Park Service, The Case of the Indian Trader: Billy Malone and the National Park Service Investigation at Hubbell Trading Post (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2011), reveals how ignorance and sloppy practices threatened the good name and livelihood of one of the most respected Indian traders in the Southwest.

This is definitely not a beach read, but if you want a gripping tale of misunderstanding and governmental indifference, this book will make an excellent airplane companion or educational entertainment. Not that it is amusing to read about a good man’s misfortune, but The Case of the Indian Trader reminds us why so much fundamental mistrust of the government and its bureaucracies exists out there. I will never look at Hubbell Trading Post with the same eyes again.

Indian Country Today

November 3, 2011

National Park Service Gone Rogue: A Whistleblower Speaks

At six a.m. on June 9, 2004, the celebrated Indian trader Billy Malone awoke to a raid on his house by National Park Service (NPS) agents. With no explanation, the agents turned Malone’s place upside down, and his world crumbled around him. His personal and working collection of Navajo rugs and jewelry was confiscated. He lost his job, was kicked out of his home and faced federal charges.

NPS investigator Paul Berkowitz took over the case a year and a half later. Dispatched to end the money-draining investigation of the Hubbell Trading Post, Berkowitz found exactly the opposite of what his superiors were asserting.

Now, in The Case of the Indian Trader: Billy Malone and the National Park Service Investigation at Hubbell Trading Post (University of New Mexico Press, 2011), Berkowitz details the unorthodox world of Indian traders and how it collided with the NPS’s twisted politics. He dissects both the government’s refusal to accept Indian culture and the resulting intrusions into centuries–old business practices that value people over the almighty dollar.

The laundry list of unethical acts and abuses of Malone by corrupt and incompetent agents, administrators and employees make one’s blood boil. The one person in this mess, aside from Berkowitz, who maintains a modicum of respect and trust in others is Malone, even as the very people charged with protecting his basic rights plot to destroy them. This inside look at how a great American institution actually undermines its own public image is as disturbing as it is necessary reading.

Indian Country Today Media Network caught up with author Paul Berkowitz to learn more about the fine art of whistle-blowing. Here’s what he had to say.

What made you want to step out of anonymity and chronicle your own account as a whistleblower?

First, the Indian trader in this story, Billy Malone, had been harmed in a very public way. He was publicly and falsely accused, publicly fired and publicly humiliated in his home community. Someone needed to take an equally public stand to expose and correct that situation. It became clear early on that no one else in the National Park Service (NPS), the Department of Justice, or the Western National Parks Association was going to step up to the plate to admit mistakes, set things right, or even offer an apology to Billy and his family. I was in a unique position to speak out and help set things right and hopefully survive the consequences of blowing the whistle on the entire situation.

Second, I’d seen this sort of thing happen before in the NPS, going back literally decades. My own efforts over the years to address those situations from the “inside,” working within the agency structure and through other government channels, had proven to be less than successful…. Again, because of my circumstances, the information I possessed and the fact that I was eligible to retire, albeit earlier than I had planned, I was in a unique position to step out of the organization and speak out publicly about what had happened at Hubbell Trading Post and about similar incidents that have happened in the past.

Read the full interview here or here. (PDF)